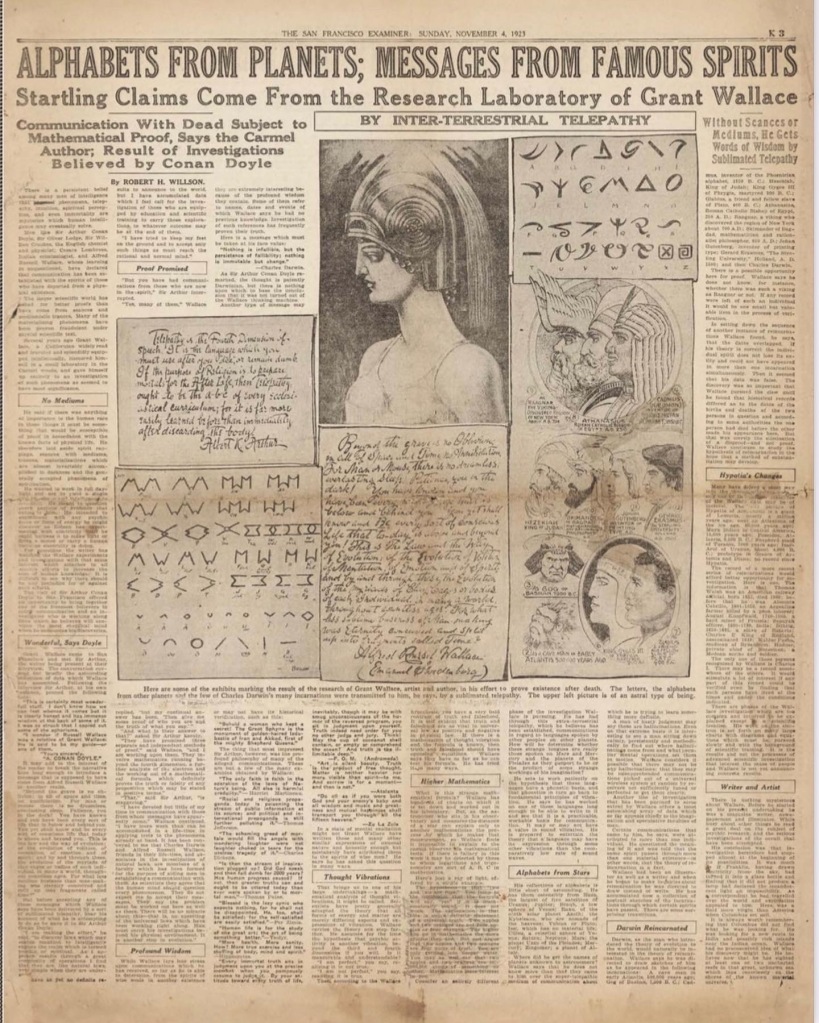

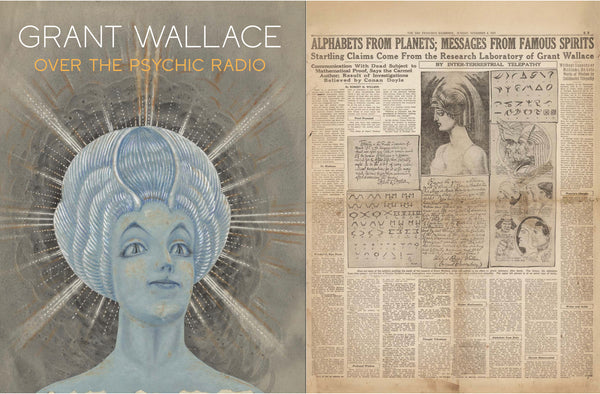

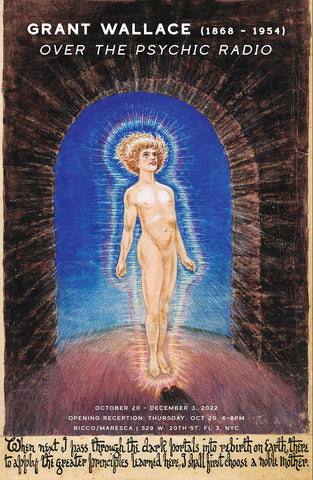

2022 Solo Gallery Exhibit in NYC

An Introduction

by Matt Berger

This message is written in thick black pencil on a scrap of paper that I keep in a handmade wooden box near my bedside, along with various keepsakes and good luck charms. It was written by my great-grandfather Grant Wallace (1868–1954), who in every sense of the word was one of history’s most famous ghostwriters.

Growing up in my conventional family household in the 1980s, my siblings and I lived in blissful innocence when it came to the otherworldly accomplishments of our mom’s dad’s dad. We did not know much about him being a spiritualist philosopher and medium to past lives, alien life forms, and spirit worlds. We mostly knew of him by my mom’s description—a famous newspaper man who collected a famous circle of friends.

Grant died in his Berkeley home when his grandchildren were young. My mom, Deirdre Wallace, was just seven years old. Her younger brother, Brian, was five. Two decades would pass before I was born, the fourth of the great-grandkids, with the surname Berger.

What I knew about Grant was mostly lore, told to me by our mom in her giddy nonchalance. In ninth grade, when I checked out Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat from the school library, she explained that the author wrote the novella while flopped out on Grant and Margaret’s living room couch for weeks in their tiny Carmel bungalow . . . she thought. “Or was it The Red Pony?” she wondered.

When we’d hike the local trails in the nearby Berkeley hills, my mom would remind us that Grant and his writer friend Jack London once invested in a eucalyptus tree importing company, until the hardwood scheme went bust and dried up our family savings account.

As an aspiring journalist, I pored over old San Francisco morning and evening edition paper newsclips by Grant that were around the house, assigned to Grant by his editors and publishers, including Fremont Older and William Randolph Hearst.

But my mom didn’t tell us much about Grant’s other journalistic endeavor—his lifelong pursuit to document “the secret structure of reality’s nine dimensions and in general set mankind straight through rational scientific method.” This I would learn from my grandfather Kevin Wallace, who detailed our family story in an unpublished memoir I found in a box in our garage when I was a teenager.

Kevin recounted Grant’s journey from his childhood home in Missouri—where Grant first reported an ability to communicate with the spirit world, once even ridding his mother of demonic possession by a monk from the time of the Spanish Inquisition—to the epicenter of late nineteenth-century modernism: New York City:

Incarnations were semesters and astral intervals holidays when ghosts with nothing better to do could communicate telepathically with those on earth and if the latter weren’t careful, hypnotize them.

Many years after his first trip to New York and living an exceptional life—settling in Carmel, California, at the suggestion of his group of friends, including Sinclair Lewis and Mary Austin; marrying a second time and starting his second family (mine)—Grant went back to Manhattan to present his most important body of work, produced under the influence of automatic writing.

But the Great Depression loomed, and Grant’s collection of bookplates and astral portraits delivered to him through “mental radio” by Pleiadian Light Bringers with names like Zu-la-zu-le, was not what his New York editors were ready to bank on.

Still, Grant continued to devote much of his life to documenting and promoting their voices. His openness as a medium, his dedication to truth, his editorial wits, and his devout family support system enabled Grant to immerse himself in his pursuit of this higher truth.

Perhaps that’s where I get it. I’ve been consumed by the resurrection of my family story for more than thirty years now, sometimes at the expense of my domestic responsibilities.

At times I wonder if it was the groundwork that Grant laid with his spirit friends that has delivered his Big Work back to New York City for this posthumous exhibition 100 years after he first presented it here. After all, it traveled a perilous journey for over a century, across country and back again, through death and inheritance, bad weather and ex-husbands, in many attics and basements. It was nearly lost entirely to a California wildfire that tore through the Sierra Nevada Mountain town where it had been stored for decades but was saved after the fire miraculously changed course.

Other times, I remember he was also among the greatest of ideas men, visionaries, and marketers of his time. Maybe this was his plot all along.

Matt Berger is a writer and producer Santa Cruz, California and the youngest of four great grandkids of Grant Wallace.